Step 1 in Basement Remodeling: Make Sure the Basement Is Dry

Whether you’re hiring a contractor or tackling a basement renovation yourself, the first rule of basement remodeling is simple: don’t start until you know the basement is dry.

Moisture problems that go unaddressed before finishing can lead to mold growth, peeling finishes, damaged flooring, and costly repairs down the road. Water seepage, water vapor, and soil gases like radon don’t stop just because drywall and flooring are installed—once trapped behind finished surfaces, these issues become harder and more expensive to fix.

Seal Basement Walls and Floors Before Finishing

Before finishing a basement, sealing the concrete walls and floors helps block moisture vapor, reduce water intrusion, and limit soil gas entry. Deep-penetrating concrete sealers work from within the concrete to reduce porosity rather than creating a surface coating that can peel or fail over time.

RadonSeal Deep Penetrating Concrete Sealer is designed for this purpose. Applied before framing or flooring, it penetrates into new or existing concrete and reacts internally to help:

-

Reduce water seepage through basement walls and floors

-

Limit moisture vapor transmission and indoor humidity

-

Reduce soil gas movement, including radon

-

Strengthen and preserve the concrete itself

The spray-on application makes it suitable for both basement remodeling contractors and DIY homeowners. RadonSeal is water-based, non-toxic, non-flammable, and emits no VOCs—making it well suited for use in enclosed basement spaces prior to finishing.

Why Basements Develop Moisture and Radon Problems

Moisture issues are one of the most common complaints among homeowners, and many basements begin to experience water seepage, elevated humidity, or musty odors within 10 to 15 years of construction. In addition, approximately one in five homes in the U.S. has elevated indoor radon levels.

These problems are not usually caused by a single defect. Instead, they result from the natural properties of concrete and how basements interact with surrounding soil over time.

1. Concrete Is Naturally Porous

Concrete contains a network of microscopic pores and capillaries formed as excess water evaporates during curing. These interconnected pathways allow:

-

Liquid water to migrate through the slab or walls under hydrostatic pressure

-

Moisture vapor to diffuse from damp soil into the basement

-

Soil gases such as radon to enter areas of lower indoor air pressure

As a result, basements are constantly exposed to moisture and soil gases—even when no visible leaks are present.

2. Concrete Chemistry and Aging Increase Vulnerability

Concrete is highly alkaline, which gradually degrades many exterior waterproofing materials and membranes. Over time, soil settlement and aging materials can allow water and soil gases to accumulate beneath the slab, increasing pressure on the foundation.

As concrete continues to age, repeated moisture exposure slowly leaches minerals from the matrix, making it more porous. This process increases the movement of liquid water, water vapor, and radon gas into the basement year after year.

For homeowners planning to finish a basement, this gradual deterioration matters. Once walls, floors, and insulation are installed, moisture and radon problems become harder to detect and significantly more expensive to correct.

Why Finished Basements Are More Vulnerable to Mold and Mildew

Moisture is a key driver of mold, mildew, and other biological contaminants commonly found in basements. Elevated humidity can contribute to respiratory irritation, allergies, and musty odors—and when moisture is present, these issues can spread beyond the basement through air movement and ventilation.

Finished basements are particularly vulnerable because many common finishing materials provide ideal conditions for mold growth. Carpet, drywall, wood framing, upholstered furniture, and fiberglass insulation can all trap moisture and supply the organic material mold needs to thrive. Once hidden behind walls or under flooring, mold problems are harder to detect and far more expensive to remediate.

The most effective way to prevent mold and mildew in a finished basement is to control moisture at its source. That means addressing water seepage and moisture vapor moving through concrete walls and floors before insulation, drywall, or flooring is installed.

Sealing the concrete foundation helps reduce capillary water intrusion and moisture vapor transmission, lowering humidity levels and creating a more stable environment for finishing. This preventative step plays a critical role in protecting indoor air quality and preserving finished basement materials over time.

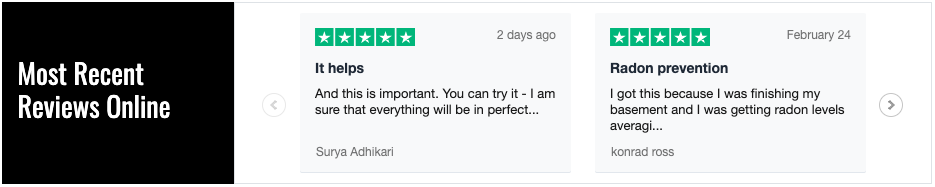

Customer feedback and tips on Sealing Damp Basements against Moisture and Molds.

Why a “Dry” Basement Still Needs to Be Sealed Before Remodeling

Even when a basement appears dry, moisture can still enter through concrete as invisible water vapor or through slow capillary seepage that isn’t immediately noticeable. Because basements are surrounded by soil, they are often the largest source of moisture entering a home.

When floors and walls are finished, this moisture becomes trapped behind insulation, drywall, and flooring materials. Over time, that trapped moisture can lead to a range of problems that compromise both comfort and durability.

Common consequences include:

-

Elevated humidity, condensation, or damp surfaces

-

Mold and mildew growth, which can spread through air movement and ventilation

-

Persistent musty odors caused by moisture interacting with organic materials

Basement finishing can be a cost-effective home improvement, but it also represents a significant investment. According to HomeGuide.com, the average cost of a midrange basement remodel was approximately $40,000 in 2022. Addressing moisture and vapor movement beforehand helps protect that investment and reduces the risk of hidden damage after the basement is finished.

Before framing or installing flooring, all below-grade concrete walls and floors should be properly sealed to limit moisture and vapor transmission. After sealing the concrete itself, joints, penetrations, and visible cracks can be sealed or caulked as part of a complete moisture-control strategy.

For homes with a history of water intrusion, additional safeguards—such as a backup sump pump—may also be worth considering as part of a comprehensive basement protection plan.

Why Concrete Chemistry Can Cause Finishing Failures in Basements

Basement moisture problems don’t just involve liquid water. Water vapor moving through concrete can carry dissolved minerals and alkalis from the slab and surrounding soil. When this moisture condenses on cooler surfaces, often referred to as “sweating”, or becomes trapped beneath finished materials, it can activate chemical reactions within the concrete.

Concrete is naturally alkaline. When moisture is present, these alkalis can interact with paints, adhesives, and floor coverings in a process known as saponification, which weakens many common finishing materials. Over time, this can contribute to:

-

Peeling or blistering paints and coatings

-

Breakdown of adhesives used for tiles, vinyl flooring, and wall panels

-

Premature failure of glued flooring systems

-

Formation of efflorescence—white mineral deposits that lift paints and tiles

These problems are especially common in finished basements, where flooring, wall coverings, and insulation trap moisture against the concrete surface.

To reduce the risk of these failures, moisture and vapor movement must be controlled before finishing begins. Treating the concrete itself—rather than relying solely on surface coatings—helps limit mineral migration, reduce efflorescence, and create a more stable substrate for basement finishes.

Deep-penetrating concrete sealers work by reacting within the concrete matrix to reduce porosity and block capillary pathways, helping control moisture, vapor, and mineral movement that can undermine finished basement materials over time.

What If Your Basement Already Has Moisture Problems?

If a basement has ongoing water seepage, dampness, or persistent humidity, those issues should be addressed before finishing the space. Covering walls or floors without correcting moisture problems often leads to mold growth, damaged finishes, and costly repairs later.

Homeowners typically consider several approaches, each with strengths and limitations.

Common Moisture-Control Options (and Their Limits)

-

Exterior foundation waterproofing can be effective but is often costly and disruptive. While it helps reduce bulk water intrusion through walls, it does little to address moisture vapor migrating up through the slab.

-

Interior drainage systems (such as perimeter drains or wall channels) are designed to manage liquid water after it enters the basement. These systems do not stop moisture or vapor from passing through concrete and may continue to release water vapor and soil gases into the space.

-

Surface waterproofing paints and coatings applied from the inside can temporarily block active seepage, but they are not designed to withstand long-term negative-side moisture pressure or vapor migration. Over time, peeling, blistering, or efflorescence can occur.

-

Plastic sheeting, epoxy coatings, and urethanes can trap moisture beneath finished surfaces. While durable in dry conditions, they are often unsuitable for concrete slabs exposed to ongoing ground moisture, where trapped vapor can eventually lead to bubbling, cracking, or odors.

-

Dehumidifiers can help manage indoor humidity, but they do not stop moisture from entering through concrete. Continuous operation also adds ongoing energy costs and does not address the underlying source of the problem.

Addressing Moisture at the Source

When foundation walls and slabs are structurally sound, controlling moisture and vapor movement within the concrete itself can be an effective part of a broader moisture-management strategy. Treating concrete to reduce capillary absorption and vapor transmission helps create a more stable environment before finishing.

After sealing and allowing the concrete to dry, additional steps—such as repairing cracks, sealing penetrations, and improving ventilation—can further reduce moisture risk. This layered approach helps ensure that finishes, flooring, and insulation perform as intended once the basement is remodeled.

(see our basement crack repair guide for details).

Common Basement Wall Finishing Mistakes to Avoid

Many finished basements are built using interior stud walls insulated with paper-faced fiberglass batts, often combined with polyethylene vapor barriers or impermeable insulation systems. While this approach has been widely used, building-science research has shown that it can create moisture problems when applied to below-grade concrete walls.

Basement walls are in constant contact with damp soil. When impermeable interior vapor barriers are installed, moisture vapor moving through the concrete can become trapped within the wall assembly. Even small air leaks can allow warm, humid indoor air to reach the cooler concrete surface, where condensation may occur. Once moisture is trapped, drying becomes difficult or impossible.

Research from building-science organizations has documented cases where interior vapor barriers in basements contributed to mold growth, decay, and persistent odors—sometimes within a short period after construction. In these assemblies, moisture introduced from the exterior or through minor leaks has no effective drying path.

Materials to Use With Caution in Finished Basements

Certain interior finishes are especially problematic in below-grade environments because they restrict drying:

-

Polyethylene or vinyl vapor barriers

-

Vinyl floor coverings with very low vapor permeability

-

OSB wall sheathing in contact with concrete

-

Oil-based (alkyd) paints and impermeable wall coverings

When finishing basement walls, assemblies should allow controlled drying while limiting moisture entry at the concrete surface. Addressing moisture and vapor movement in the concrete before adding insulation and finishes is a critical step in avoiding long-term performance problems.

How to Build Interior Basement Walls the Right Way

Uninsulated basements can be a significant source of heat loss, especially in homes where the basement is connected to the conditioned living space. Because below-grade foundation walls remain in contact with the ground year-round, energy guidelines and building codes generally recommend insulating basement walls as part of an energy-efficient home.

Rather than a single universal R-value, recommended insulation levels for basement walls vary by climate zone and by the type of insulation assembly used. Modern energy codes such as the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) provide guidance that many builders and remodelers use as a reference.

Recommended Basement Wall Insulation Levels

Typical code-based targets for conditioned basements include:

-

Climate Zones 3–4

• Continuous insulation: R-5 to R-10

• Cavity insulation equivalent: R-13 -

Climate Zones 5–6

• Continuous insulation: R-10 to R-15

• Cavity insulation equivalent: R-15 to R-19 -

Climate Zones 7–8

• Continuous insulation: R-15 or greater

• Cavity insulation equivalent: R-19 or greater

These ranges reflect common compliance paths and increase with colder climates. Because basement walls behave differently than above-grade walls, insulation performance should always be considered together with moisture control and drying potential, not R-value alone.

Exterior vs. Interior Basement Wall Insulation

Exterior insulation is often considered the most robust solution because it keeps foundation walls warm, reduces condensation risk, and allows the concrete to dry toward the interior. However, it is rarely practical for existing homes due to excavation costs, risk of damage during backfilling, and concerns related to insects and long-term durability.

For most basement remodeling projects, interior insulation is the practical choice—but it must be designed correctly.

Key Principles for Interior Basement Wall Construction

When insulating basement walls from the interior, successful assemblies share a few important characteristics:

-

Materials must be moisture-tolerant

-

Assemblies should allow controlled drying, rather than trapping vapor

-

Warm, moisture-laden indoor air must be prevented from contacting cold concrete surfaces

For these reasons, modern basement assemblies emphasize an air barrier, not an impermeable interior vapor barrier.

Insulation materials commonly used in basements—when detailed correctly—include:

-

Unfaced rigid foam insulation (extruded or expanded polystyrene)

-

Closed-cell or open-cell spray foam systems

-

Unfaced batt insulation when separated from direct concrete contact

A Practical Approach to Finishing Basement Walls

A reliable method for finishing basement walls begins with controlling moisture at the concrete surface before insulation or framing is installed.

A typical sequence includes:

-

Seal the concrete foundation walls to reduce water seepage and moisture vapor transmission.

-

Install rigid insulation (often 1–2 inches) directly against the wall, sealing seams to limit air movement.

-

Add framing or furring to support drywall and optional additional insulation.

-

Install fire-rated drywall as required by code, using vapor-permeable interior finishes such as latex paint.

-

Avoid interior polyethylene vapor barriers, vinyl wall coverings, or other impermeable materials that can trap moisture.

An alternative approach is to build a framed wall slightly away from the concrete surface using unfaced insulation, leaving space for limited drying—provided the concrete itself has been properly sealed first.

Why Preparation Matters

Regardless of the insulation strategy used, controlling moisture and vapor movement before finishing is critical. Once insulation, drywall, and flooring are installed, correcting moisture problems becomes far more disruptive and expensive.

By addressing moisture at the concrete surface first, interior basement wall assemblies are more durable, more energy-efficient, and far less likely to experience mold growth, odors, or finish failures over time.

Radon Gas Considerations When Finishing a Basement

Basements are a common entry point for radon gas, and changes made during basement remodeling can sometimes affect indoor radon levels. Sealing walls, adding insulation, altering airflow, and increasing occupancy in finished basement spaces can all influence how radon behaves inside a home.

In some cases, homeowners discover elevated radon levels after finishing a basement—when testing is repeated or when a finished lower level becomes a primary living area. If radon levels exceed the EPA’s recommended action level of 4.0 pCi/L, mitigation may be required to maintain indoor air quality and preserve resale value.

Once a basement is finished, installing a fan-based radon mitigation system typically involves additional cost and disruption. Vent piping and fans must be routed through finished spaces, and installation options become more limited compared to treating the concrete foundation beforehand.

For families planning to use a finished basement as living space—especially where children spend significant time—addressing radon pathways early is an important part of remodel planning.

Sealing concrete walls and floors before basement remodeling helps reduce soil gas entry points and can lower baseline radon levels or improve the effectiveness of any future mitigation measures. While sealing alone may not eliminate radon in every home, it can play a valuable role as a preventive step that simplifies long-term radon management.

Flood Protection and Contingency Planning for Finished Basements

When finishing a basement, it’s important to plan not only for everyday moisture control, but also for unexpected water events. Leaking appliances, plumbing failures, overflowing fixtures, or heavy surface runoff can introduce water into a basement even when the foundation itself is sound.

Because finished basements contain flooring, drywall, insulation, and furnishings that are sensitive to water, interior finishes should be selected with potential water exposure in mind. Using moisture-tolerant materials and avoiding assemblies that trap water can help limit damage if a leak or overflow occurs.

For homes with sump pumps, adding a backup sump pump provides an extra layer of protection. Backup systems help maintain pumping capacity during power outages or primary pump failure—two common causes of basement flooding during storms.

Whether powered by water pressure or a battery system, backup pumps installed above the normal sump water level can improve reliability and reduce the risk of extensive damage to a finished basement.

A Preventive Approach to Basement Remodeling

A finished basement must withstand more than just everyday use. It has to manage moisture, water vapor, and soil gases like radon—all while supporting insulation, drywall, flooring, and furnishings that are far less forgiving than bare concrete.

Addressing these issues before remodeling begins is far easier and more cost-effective than correcting problems after walls and floors are finished.

As an early step in basement preparation, sealing the concrete walls and slab helps reduce water seepage, limit moisture vapor transmission, and restrict soil gas entry. Treating the concrete itself before framing or flooring is installed protects finished materials, preserves the foundation, and reduces the likelihood of costly repairs later.

A prevention-first approach allows a basement remodel to perform as intended—providing durable, comfortable living space while minimizing long-term maintenance and indoor air quality concerns.